To read this update in its original PDF format please click here

Memo to: MCJ Capital Partners

From: M. Carter Johnson

Re: Q4 2022 Performance Update

Date: 1/30/2023

Dear Partners & Friends,

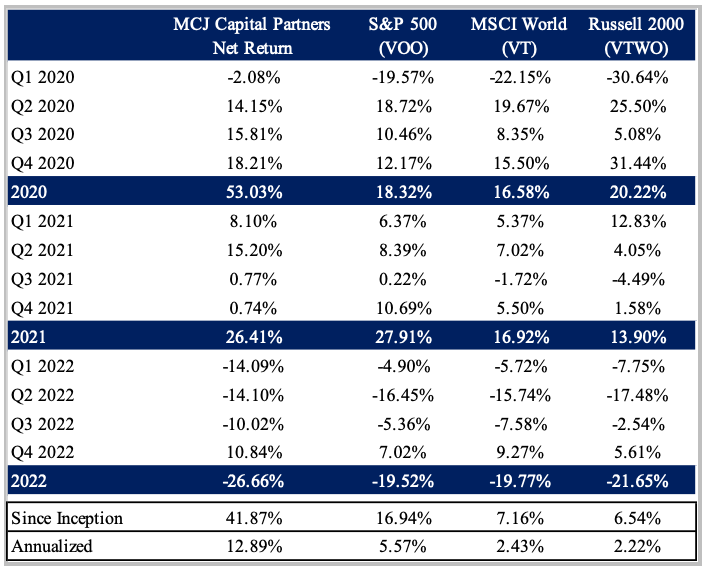

For Q4 of 2022 our total return was 10.84% compared to 7.02% for the broader S&P Index, 9.27% for the MSCI World index, and 5.61% for the Russell 2000 index.(1)

For 2022, our total return was -26.66% compared to -19.52% for the broader S&P Index, -19.77% for the MSCI World Index, and -21.65% for the Russell 2000 index.

Since inception (as marked February 12, 2020), our total return is 41.87% compared to 16.94% for the broader S&P Index, 7.16% for the MSCI World index, and 6.54% for the Russell 2000 index.

Thoughts and Commentary on 2022

In a historical context, 2022 was a no good very bad year for investors. There has been only three times since 1926 that both U.S. Stocks and Bonds recorded negative returns simultaneously. Those years were 1931, 1969 and now 2022. Over that same time span, on only six occasions have returns for the S&P 500 been worse than the last year. Said differently, a year like last (or worse) comes along roughly once every 30 years if you’re invested in a bond and equity portfolio, and a little more than once every 20 years for an equity portfolio.

The good news is when markets decline to the magnitude witnessed in 2022, it’s rare to have the following year proceed with further decline. Only in 1930 did the S&P 500 fall 24.90%, with an encore follow up decline of 43.34% in 1931. That year aside, most proceeding years treated investors quite favorably. The 35.03% decline of 1937 was followed by a 31.12% climb in 1938. The 26.74% drawdown in 1974 was followed by a 37.20% ascent in 1975. The 22.10% drop of 2002 was met with a 28.68% rally in 2003. And finally the 37% drop of 2008 was followed by a positive 26.46% return in 2009. All this to say nothing is certain, however if you are betting base rates you’re probably leaning into the possibility of 2023 being a better year than last.

On Management

I was recently asked how I assess management and it reminded me of a great story from Edwin Lefèvre’s 1923 classic Reminiscences of Stock Operator. The story centers around a wise investor identified as the Pennsylvania Dutchman and what he observed when visiting management of two different companies. In the words of the Pennsylvania Dutchman:

"I noticed that President Reinhart, when he wrote down figures, took sheets of letter paper from a pigeonhole in his mahogany roll-top desk. It was fine heavy linen paper with beautifully engraved letterheads in two colors. It was not only very expensive but worse it was unnecessarily expensive. He would write a few figures on a sheet to show me exactly what the company was earning on certain divisions or to prove how they were cutting down expenses or reducing operating costs, and then he would crumple up the sheet of the expensive paper and throw it in the waste-basket. Pretty soon he would want to impress me with the economies they were introducing and he would reach for a fresh sheet of the beautiful notepaper with the engraved letterheads in two colors. A few figures and bingo, into the waste-basket! More money wasted without a thought.

It so happened that I had occasion to go to the offices of the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western a few days later. Old Sam Sloan was the president. His office was the nearest to the entrance and his door was wide open. It was always open. Nobody could walk into the general offices of the D. L. & W. in those days and not see the president of the company seated at his desk. Any man could walk in and do business with him right off, if he had any business to do. The financial reporters used to tell me that they never had to beat about the bush with old Sam Sloan, but would ask their questions and get a straight yes or no from him, no matter what the stock-market exigencies of the other directors might be.

When I walked in I saw the old man was busy. I thought at first that he was opening his mail, but after I got inside close to the desk I saw what he was doing. I learned afterwards that it was his daily custom to do it. After the mail was sorted and opened, instead of throwing away the empty envelopes he had them gathered up and taken to his office. In his leisure moments he would rip the envelope all around. That gave him two bits of paper, each with one clean blank side. He would pile these up and then he would have them distributed about, to be used in lieu of scratch pads for such figuring as Reinhart had done for me on engraved notepaper. No waste of empty envelopes and no waste of the president's idle moments. Everything utilised (sic).”

The Pennsylvania Dutchman goes on to explain how his capital invested in D. L. & W. quadrupled thanks to his ability of identifying the economically conscious manager, old man Sloan.

When I read that story as a young teenager it was the first exposure I had to the idea that subtle observations and assessments of management could create an edge in an investment process. Over time, my model of assessing management has evolved. It’s certainly a never ending exercise of refinement that will continue to change. What I’ve come to realize is when I assess management I’m typically trying to answer five main questions:

1) Do they have a clear passion and love for the game?

2) Do they possess a behavioral advantage?

3) Do they think long-term?

4) Do they have above average operational skills? and / or

5) Do they have above average capital allocation skills?

In a way these components feed into each other and reinforce a fly wheel of sorts. Let’s break these down further...

Clear Passion and Love for the Game

One of the biggest advantages in investing is partnering with managers who have a genuine passion and love for the game. Passion outlast natural talent. Passion works relentlessly to improve. Passion is process oriented. When you find a passionate manager their love for the work pulls them towards the business.

Questions to assess:

What language do they use when they talk about the business? The language, the tone, the expressions used when management talks about the business can be one of the biggest indicators as to how passionate they are about what they do.

Do they reference who they studied and how they emulate what they’ve learned? Passionate managers are never ending students of their game. They study other greats. They break down what they learn. They try different styles and techniques to incorporate in their own work. They experiment. They adapt best practices without ego as to who came up with the original idea.

Do they support colleagues with enthusiasm and let them share the spotlight? Passionate managers operate with an inner confidence and security. They’ll let other executives and managers share wins and operate with a sense of independence. Passionate managers are rarely insecure or threatened by one of their lieutenants. They share the spotlight.

Do they recruit and retain talent from other companies they admire? Passionate leaders want other above average players on their team. In addition, above average players usually want to work with above average leaders. Passionate leaders have a way of identifying and recruiting high tier talent to help them execute on the overall strategy.

Do they think multi decades or how the business will survive beyond their tenure? When you find a passionate leader you’ll notice the business transcends beyond them. They’re able to explain and focus on enduring competitive advantages that pay dividends beyond their time with the company. It’s less about them and what they can accomplish, and more about what they can contribute to the long run of the business.

Most managers are hired hands employed by the highest bidder to crank out the next best quarter. Passion driven managers are different. They often take more of a craftsman approach, and are less inclined to make short-term decisions that threaten the long-term durability of the business. If you partner with a manager that is truly passionate about what they do, typically the business is in good hands.

Behavioral Advantage

It isn’t enough for managers to possess passion. The reality is business can be messy. Management has to navigate economic cycles, business cycles, and market cycles. In addition there’s the never ending demands of customers, suppliers, employees, shareholders, community advocates, industry associates, all with varying priorities. At any given point there’s enough happening to jerk anyone into a reactive state. However, the best managers maintain a behavioral advantage. This allows them to quiet the short-term noise and keep course on what needs to be done for the business to succeed long-term.

Questions to assess:

Do they have a significant ownership stake? Partnering with management that has significant ownership and a history of not taking advantage of their shareholder base is the holy grail. If they bought their shares (or continue to buy) on the open market, that’s even better. When you have management that owns a significant stake there’s less politics and pageantry to appease short-term critics. They can focus on managing the business versus managing for short-term improvements in share price.

Are they showing significant signs of lifestyle creep? If management has a significant ownership stake the biggest threat of stealing their focus comes from significant lifestyle creep. Lavish lifestyles need funding, and if scaling up on the home front happens too fast it can put the manager at a significant behavioral disadvantage. All of a sudden decisions become short-term focused. Results don’t materialize fast enough. What the stock price did today matters more than what is being done in the business.

Does their capital structure give them an advantage across the entire business cycle? We want managers to operate on strategic initiatives that grow the intrinsic value of the business over the long-term. If the capital structure is less than ideal, management is at the mercy of others. This puts them at a disadvantage at various points of the business cycle. On the contrary a good capital structure means management can act boldly when others are timid. The ability to act bold in timid times is a superior behavioral advantage.

Have they attracted the right shareholder base? Good managers attract a good shareholder base. Earning the trust of a patient shareholder base creates a wonderful advantage for management to operate through challenging environments. To the contrary, if management has the wrong shareholder base, they’ll be more tempted to ante company resources for quick wins in an effort to keep their title.

At the end day businesses are ran by people. People with hopes, dreams, fears and aspirations. People with emotions. What we aim to identify in a behavioral advantage is leadership that won’t let the ups and downs of the business (or stock price) drive irrational action that could be a detriment to the company.

Think Long-Term

The pinnacle of great management is the ability to think long-term. It’s more difficult than it sounds. Thinking long-term requires delayed gratification. It means putting off the rewards of today for a better tomorrow. The average executive tenure is just 4.9 years making true long-term thinking a risky career proposition. Yet in a world obsessed with the next quarter, long-term thinking creates an unfair advantage. Long-term thinkers can implement different strategies that their short-term thinking counterparts wouldn’t dream. And it’s the thinking long-term that drives sustainable value creation.

Questions to assess:

Do they operate with high integrity? This is a pretty easy one as anyone that lacks integrity simply doesn’t understand the big picture enough to have consideration to the long-term implications. Red flags in this area are a great way to eliminate a business early in the due diligence process.

Do they reinforce supply lines? History is filled with examples of military initiatives that failed drastically because of unreinforced supply lines. In business, “reinforcing supply lines” means building the non-sexy infrastructure to support the sexy growth. Short-term thinkers are quick to expand but fall into the trap of overextending without supporting the new growth. Long-term thinkers aim to make expansion permanent. When growth occurs, the business is given what is needed to sustain the new market.

Are they consistent in how they present the business? Changes in how the business is presented shows wavering priority. Long-term thinkers have a consistency about how they present what’s happening to the business, how it’s improved or declined in comparison to prior periods, and why it’s still important for long-term value creation. Changes in how the business is presented will occur, but it shouldn’t be happening every year (much less every quarter).

How do they react to missteps? Along the journey missteps are certain. Long-term thinkers understand this and address the issues with transparency and new takeaways. Short-term thinkers overreact and shift blame to others or circumstances outside of their control.

Do they plant Pine Trees or Bamboo Shoots? Bamboo can grow as fast as 1.5 inches an hour. Pine trees grow less than one foot a year. If we have a bamboo forest it won’t be long until the competition has its own bamboo forest. What we want is management with a forest of pine trees and a knack to keep planting more pine trees. For example, several of our serial acquirers have spent multiple decades nurturing relationships for just that moment when the current owner is willing to part with their business. We also have businesses that have spent multiple decades securing land for geographical advantages. These are pine trees planted by management. Time is one true moat.

If our aim is to own good businesses for long stretches of time, its only logical to partner with managers who prioritize what’s best for the company over the long-term. This means forgoing easy but fleeting short-term wins. It requires often doing what is unpopular. It demands showing up day after day to grind on the small tasks that keep expanding the longevity of the organization.

Above Average Operational Skills

Good operators can do more with less allowing them to create superior returns on their asset base. Most durable competitive advantages are born from above average operators executing persistently in the early days. As a business grows, the great operators have a way of remaining in tune with what’s occurring in the day to day operations of the business.

Questions to assess:

Are they process driven? Taylorism, Kaizen, Lean Methodologies all have similar components in which there’s a virtuous cycle of never ending improvement. The betterment of the process is a process itself. Operators with above average skillsets are process driven, looking for continuous incremental improvements across the entire business system.

Do they understand and articulate constraints of the business? Good management who is in touch with operations understand the bottlenecks and constraints of the business in its current form. They can articulate what constraints need to be removed for the business to accelerate growth or get to the next milestone of focus.

Do they recognize when to prioritize growth and when to prioritize margins? Some managers prioritize growth at all cost, other managers are great at expanding margins for bottom line growth. Extraordinary operational managers can throttle between the two, understanding which type of growth is more advantageous to the business at that point in time.

Are they customer focused? A funny thing happens in business, when you take care of your customers you tend to do well. Great operators make decisions within the business system that prioritize the customer’s needs.

Have they embedded a “company” approach to the way things are done? Good operators take pride in how things are done. They’ll often refer to operating standards and how things are done within the business in a branded manner.

The younger the business, the more important operational skills are in comparison to capital allocation skills. A young company is still shaping the core components of the business model. In addition, good operators have the advantage of being able to plow more cash flow back into what they know - operations. As the business matures a good operator is inevitably forced to consider other avenues of allocating capital.

Above Average Capital Allocation Skills

What makes capital allocation so challenging is that most managers never procure experience at it until they’re hoisted into the head position. Few businesses drive capital allocation decisions down within the organization. Therefore most managers allocation skills are unfairly given a trial by fire test. This is one of the reasons so much capital is diminished in business. Yet, over the long run return on capital is what drives growth of intrinsic value within a firm.

Questions to assess:

Do they avoid make or break allocations? Great allocators avoid initiatives that “make or break” the entire company. Great allocators take a lot of small swings building lessons from each experience over time. If an allocation decision doesn’t work it doesn’t set the business off course.

Can they invest up and down the balance sheet? Good capital allocators aren’t one trick ponies. Good capital allocators know where value is hidden on the balance sheet. They know how and when to manipulate the cash conversion cycle. They know when to use leverage and when to pay it down. They know when it’s better to tap equity funding and when it’s favorable to retire shares. The best are good at creating value through their capital structure.

Have they made capital allocation a cultural component? As previously mentioned, rarely is capital allocation pushed down within an organization. Superior capital allocators understand the benefit of making capital allocation a cultural component of the organization.

Do they lean into their advantage? Good capital allocators know where they have an advantage in their capital allocation process. For serial acquirers, the acquisition process is a core competency. For superior operators, investing internally usually has its advantages over competing for outside acquisitions. In more cyclical businesses good allocators know which levers offer value at which point across an entire cycle. Advantages vary from company to company, but good capital allocators know what to lean on.

Do they articulate how capital decisions flow through the financials? Management that knows how to allocate capital can walk you through how those decisions flow through the financials. Their thoughts are organized and concise. They can articulate with clarity how the capital allocation decision should impact the entire entity.

The longer we hold our companies the heavier the capital allocation decisions made by management will impact our returns. Partnering with superior capital allocators in management is almost a cheat code in investing.

As It Relates To Our Companies

Our trust in management is of particular importance during years like 2022. Looking over our roster I think we have a superior group of managers. When I look for good companies, the assessment of management comes only after finding attraction in the underlying business. Ironically, our portfolio features great management and yet that was never the targeted objective. This leads to a question I still haven’t been able to fully answer - does the business make the manager or does the manager make the business? I think it’s a little of both.

In Closing

What’s important during a drawdown like 2022? For me over the year I found myself primarily revisiting four items:

1) Clarity in our theses – Do we know why we own what we own? Are we clear on the few crucial points that really matter? Does what’s occurring permanently impact those points?

2) Humility to recognize where we might be wrong – I was certainly wrong on a number of fronts. The most glaring and obvious in retrospect was the margin durability for a few of our smaller companies. I also mis-assessed the turnaround time needed to pass along rising costs to end customers. In addition, I’d encourage you to revisit our 2022 Q3 update where I further listed a number of items where I was wrong.

3) Conviction in the underlying business – Stock prices move around a lot. Changes to the business do not. What we are buying is ownership in companies. As owners we’ve bought these stakes knowing not every year is going to be smooth sailing. For some of our companies my conviction grew stronger in the underlying business.

4) Trust in management – I was pleased with how our management navigated last year. I also grew my appreciation in the ingenuity of a few specifically.

We’re going to have years like 2022. Fortunately, drawdowns give us a chance to upgrade the portfolio. It also gives me a chance to learn. I continue to be grateful for your trust in managing your capital and look forward to what is ahead.

Until next time,

M. Carter Johnson

1) The performance results shown are those of the first account under management of MCJ Capital Partners LLC (“MCJ”) and are the result of the application of MCJ’s proprietary investment process. These performance results are presented net of all fees including brokerage, margin, custodial, and a 1% management fee beginning in January 2021. No management fee was charged in 2020, all other fees were present. A client’s return with respect to an investment would be reduced by any fees or expenses a client may incur in the management of its investment advisory account, including advisory fees in the future. The performance results include the reinvestment of dividends and interest on cash balances where applicable.

All performance results are unaudited and are not an estimate of any specific investor’s actual performance, which may be materially different from such performance depending on numerous factors. No representations or warranties whatsoever are made by MCJ or any other person or entity as to the future profitability of an investment account or the results of making an investment. All information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed as advice in relation to legal, taxation, or investment matters. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Each of the S&P 500 Index, the MSCI Index, and the Russell 2000 Index (each, an “Index”) is an unmanaged index of securities that is used as a general measure of market performance, and its performance is not reflective of the performance of any specific investment. The Index comparisons are provided for informational purposes only and should not be used as the basis for making an investment decision. Further, the performance of an account managed by MCJ and each Index may not be comparable. There may be significant differences between an account managed by MCJ and each Index, including, but not limited to, risk profile, liquidity, volatility and asset comparison. The performance shown for each Index reflects no deduction for client withdrawals, fees or expenses. Accordingly, comparisons against the Index may be of limited use. Investments cannot be made directly into an Index. The S&P Index return was determined using the performance of Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO). The MSCI Index return was determined using the performance of Vanguard Total World Stock ETF (VT). The Russell 2000 Index return was determined using the performance of Vanguard Russell 2000 ETF (VTWO).

MCJ offers investment advisory services and is registered with the state of Colorado. Registration does not constitute an endorsement of the advisory firm by the Colorado Securities Commissioner nor does it indicate that the advisory firm has attained a particular level of skill or ability. All content on this webpage is general in nature, not directed or tailored to any particular person, and is for informational purposes only. Neither this webpage nor its contents are offered as investment advice and should not be deemed as investment advice or a recommendation to purchase or sell any specific security. In addition, neither this webpage nor its contents should be construed as legal, tax, or other advice. Individuals are urged to consult with their own tax or legal advisers before entering into any advisory contract.

The information contained herein reflects the current expectations and opinions of MCJ as of the date of publication, which are subject to change without notice at any time. MCJ does not represent that any expectation or opinion will be realized. While the information presented herein is believed to be reliable, no representation or warranty is made concerning the accuracy of any data presented. Neither MCJ nor any of its advisers, officers, directors, or affiliates represents that the information presented in this tear sheet is accurate, current or complete, and such information is subject to change without notice. No representations or warranties whatsoever are made by MCJ or any other person or entity as to the future profitability of an investment account or the results of making an investment.

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Additional information is available from MCJ upon request. MCJ is not acting as your adviser or agent unless and until you and MCJ sign an investment advisory agreement.

Readers are advised that the material herein should be used solely for educational purposes. This memorandum expresses the views of the author as of the date indicated and such views are subject to change without notice. MCJ Capital Partners LLC does not purport to tell or suggest which investment securities members or readers should buy or sell for themselves. Readers should always conduct their own research and due diligence and obtain professional advice before making any investment decision. MCJ Capital Partners LLC will not be liable for any loss or damage caused by a reader's reliance on information obtained in any of our newsletters, presentations, memorandums, special reports, email correspondence, or on our website. Our readers are solely responsible for their own investment decisions.

The information contained herein does not constitute a representation by the publisher or a solicitation for the purchase or sale of securities. Our opinions and analyses are based on sources believed to be reliable and are written in good faith, but no representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness. All information contained in our newsletters, presentations or on our website should be independently verified with the companies mentioned. The editor and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions.